I’ve been watching a number of Chinese movies lately ("Curse of the Golden Flower," "Fearless," and "House of Flying Daggers" being at the top of the list of movies y’all have probably heard of and could easily access), and all I can say is . . . I’m picking up on a pattern.

I’m not trying to play the spoiler here or anything, but here’s a big one for any of you that are choosing to watch a Chinese movie anytime soon: the protagonist dies. Or the protagonists (plural) die. If there are lovers, it’s going to be unrequited, and they’re going to die. Okay? At best, all the best-laid plans will fail, and everyone will be tragically disillusioned and heartbroken at the end.

There you have it. Pretty different from the "Goodguy Always Wins*" films in the States, yeah?

And I’ve been trying to piece together why this is the case (because this is actually a pattern I picked up on many years ago, but I didn’t know enough about real Chinese culture to try to figure it out). One of my theories is about recent history:

For the last 150 or so years, China has been a whipping-boy for various world-leading countries. Beginning around the Opium War, Chinese was humiliated and slapped around by the West (France and Britain, mostly, but others got in on the fun) and Japan for decades. Then, after World War II, as those powers kind of backed off a bit to lick their wounds, China decided to slap itself around. I’m not going to go too deeply into the history here (that’s for another day, when my e-mail isn’t being read by that same government), but let’s just say that Mao’s regime didn’t exactly change the Chinese people into dreamers and hopeless romantics.

No, instead, for a couple decades Chinese folks learned that anybody – including the closest family members – could sell you out. They learned that the most brutal and mean-spirited people were the most likely to move up; and they saw all the attempted heroes who stood up and said "enough" get killed, humiliated, and then posthumously tarnished.

Only in the last decade has that started to change a bit. I can feel it. The people aren’t scared the way I imagined they would be (or that I imagined they used to be). They don’t express hopelessness as a given. I actually have met numerous "country-folk" who used to be literal peasants and who have now worked their way up the ladder. Things aren’t perfect, not in the slightest, but they aren’t as desperately tragic (at least not for everybody).

That said, after generations of the hopeless kind of history, could you blame the people for feeling that the only true heroes die in the end? Or that true heroism is standing up and fighting when you know you can’t possibly win?

In this context, it makes sense to me.

But it may not actually be that simple. Because another clue is hidden in the language**, and only recently have I been in a position to understand it. It goes like this:

The word for "past" is the same word for "front." The word for "future" is the same word for "back." Right – exactly the opposite of how the terms are used in English. In English, we "face the future," and "leave the past behind us."

Not so the Chinese (and likely other peoples of the world, but I don’t know who, presently). Why? Because you can readily see the past, it’s already happened, so we can know all about it – just like the terrain right in front of you; you can see it. The future? Unknown. Hard to see clearly (if at all), like that which is behind you.

It actually kind of makes more sense than the English way of looking at it.

That said, it also says so much about the differences between these two cultures and the way they view the world and life. Because if you’re constantly looking towards the past, it’s hard to move on. It causes you to tie more importance to your ancestors and those who’ve come before you. If the past is what’s always in front of you, then everything you do hinges on it, and pasts are often full of mistakes. On the other hand, if the future is behind you and completely unseeable and unknowable, then fate and acceptance are going to be stronger players. "Mei banfa"*** – "there is no choice/other way." The future deals what it deals, and we have to subsequently deal with that. Acceptance. And martyrdom.

On the flip, we English-speakers (I’ll stick to U.S. citizens here, because I know them) are all about "looking to the future." We can "see" our futures, because we’re the ones who make it. We "make our own destiny." We put the past behind us and move on, not allowing it to tie us down or keep us from doing things. We can "do anything if we put our mind to it." It’s a very proactive, positive way of thinking. It allowed the English-speaking cultures to become the "go-getters" that we are, and led to their current domination of the globe (among other things).

But it’s got its flaws, as well. Because it certainly doesn’t breed a sense of "acceptance." If things don’t work out our way, we often cry about it, instead of stoically accepting. The Chinese way of thinking may be more melodramatic in some ways, but its got its strengths, as well.

So we take these ways of thinking and apply it to movies and – BOOM – solid theory we have: the "goodguys/girls" in our English-speaking U.S. culture create their own destiny and succeed against all odds – because that’s their power and strength. The "goodguys/girls" in the Chinese culture fight on yet die in the face of overwhelming odds – because that’s their power and strength. And, right there – you’ve got a great basis for analyzing the difference between these two worlds. Just imagine the various ways (small and big) in which that framework could have a bearing on an entire culture and its history . . . ****

And so I ask my fine readers from other cultural backgrounds (or who just watch lots of foreign films) – what’s the mind-set of other cultures on this matter? What other cultural mentalities are you all aware of that are displayed in a people’s language? Do my "theories" stand up to further inspection, or do some of you have knowledge that proves me full of it? I hope some of you chime in on this one, because I find this stuff fascinating.

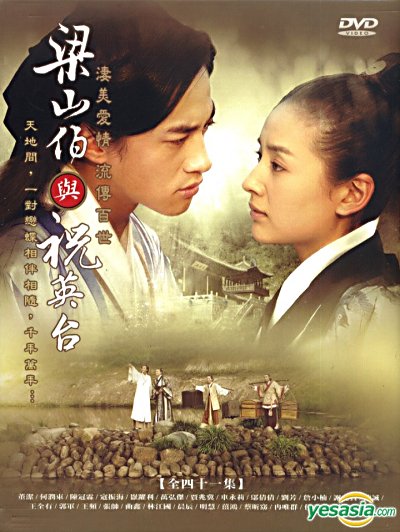

Oh, and if you end up watching "the Butterfly Lovers" (the story pictured here), sorry for spoiling the ending . . .

* There’s a reason I left that as only goodguys for the "American" films . . .

** At some point I will have to write a post on the effects of speaking a language on the way in which a person thinks . . . there’s all sorts of interesting research on the topic, and I’ve experienced a lot of it, myself (Chinese is my fourth language).

*** To those pinyin-knowledgeable folks cringing at the lack of tones on that one – my e-mail just doesn’t do Mandarin tones, so I did none, to avoid having a couple not-quite-right ones . . .

**** Of course, there are always exceptions to the rule. Do I need to say more, though?